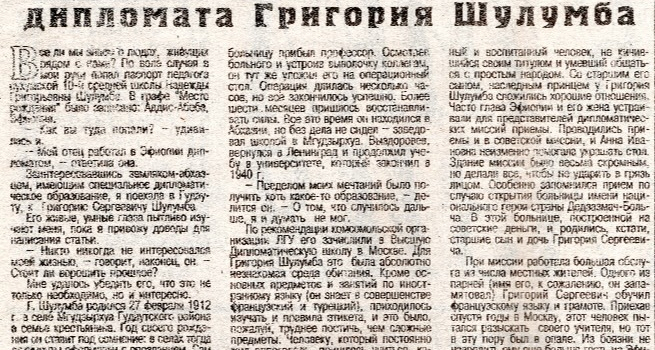

A boy from an ordinary Abkhazian family dreamed of studying, and then was in different countries, found a wife in Central Asia and took her to Ethiopia. Diplomat Grigory Shulumba did not like to talk about work and life, but we remember and know about him.

Asta Ardzinba

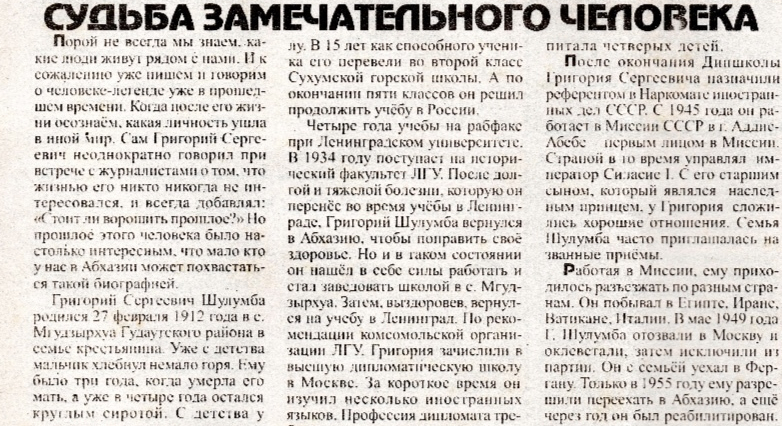

Grigory Shulumba is a Soviet diplomat of Abkhazian origin. He was born in 1912 in the village of Mgudzyrkhua, Gudauta district, in a peasant family. In early childhood, the boy was left an orphan; he was taken care of first by his grandmother, and then, when she was gone, by his aunt, his father's sister.

Education among farmers, village life and its usual way of life - it seemed that Grisha's fate was very predictable and predetermined. The aunt saw no other prospects for him than to work with land. However, in fact, social events and unprecedented hills of distant African Ethiopia were waiting for Gregory. Could he then dream about it, and how did it happen?

Capable and purposeful

An unexpected turn in his life happened one day: his maternal uncle, Mancha Ardzinba, took the boy to his relative Data Gaguliia in the village of Lykhny. He invited them to work with children - these were his own two daughters, Grisha and another nephew - a Russian nun who taught them all to write and read in Russian, taught mathematics.

Grisha excelled in his studies: he really liked to study. Soon he was accepted into the Gudauta Abkhazian School, and at the age of 15, as a capable student, into the second grade of the legendary Mountain School in Sukhum. Shulumba studied there for five years, after which he left for Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) with a referral from the Narkompros (People's Commissariat of Education - ed.) of Abkhazia. In the city on the Neva, he first studied at the workers' faculty (workers' faculty - a special faculty for the accelerated preparation of workers and peasants for higher education - ed.) at the then Leningrad State University (now St. Petersburg State University - ed.), and then entered the history department of the university and graduated from it.

Something happened that he did not think about

Few articles have been written about Grigory Shulumba, there is almost no information about him online. He himself gave only a few interviews. In them, a well-known diplomat admits that the limit of his dreams in his youth was only to get an education, he could not even think about what happened next.

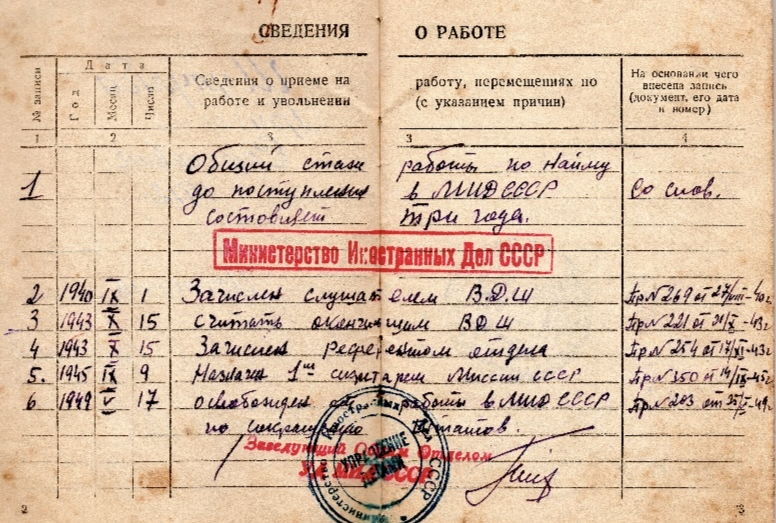

It happened that after graduating from the university in 1940, on the recommendation of the Komsomol organization of the Leningrad State University, he was enrolled in the Higher Diplomatic School under the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs of the USSR (NKID USSR). Grigory moved to Moscow.

He was about to go to the front when the Great Patriotic War began, but he was returned: the students of the Diplomatic School received a reservation. They were evacuated to the city of Fergana, Uzbek SSR.

In this city, Gregory met his future wife, nineteen-year-old Anna. She became his reliable support and friend of the heart for the rest of his life. Together they raised four children.

Beginning of the career

After graduating from the Diplomatic School, Grigory Shulumba was appointed assistant to the Middle East Department of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs of the USSR. He worked in this position until 1945, before being appointed First Secretary of the USSR Mission in Ethiopia. There he had a very difficult time, and not because of the complexity of the work.

Grigory Shulumba, in a statement addressed to Boris Pugo, Chairman of the Party Control Committee under the Central Committee of the CPSU, described such a case: "The then People's Commissar of Education of Georgia, Kiknadze, was appointed People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs of Georgia. Once Kiknadze invited me to his office (Department of the Middle Easter of the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs). After greeting me, Kiknadze asked how I got into the NKID. Then he offered me to go to Georgia to work. I did not agree. Soon I was summoned to the head of the NKID Office of Personnel Silin M.A., who at first persuaded me in a normal tone, then finished in a rude manner.

Kiknadze did not abandon attempts to, in fact, exile Shulumba to Georgia, he even threatened that it would be worse if Grigory did not agree. Other methods also were used. Without Grigory’s knowledge, he was sent to the disposal of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs of the Azerbaijan SSR. It got to the point that the young diplomat wrote a statement about his release from work in the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs of the USSR in the name of the Personnel Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR Dekanozov. He, after listening carefully, replied that the order to appoint Shulumba to the NKID of the Azerbaijan SSR would be canceled, and he would continue to work in his former place.

Soviet mission in Addis Ababa

Grigory Shulumba came to Ethiopia in September 1945 and stayed in this African country until May 1949 - first as the first secretary of the USSR Mission in Addis Ababa, then as a chargé d'affaires, that is, the first person in the Mission. At that time, the Soviet Union pursued a policy of promoting socialism in other countries, providing humanitarian and, in some places, military assistance.

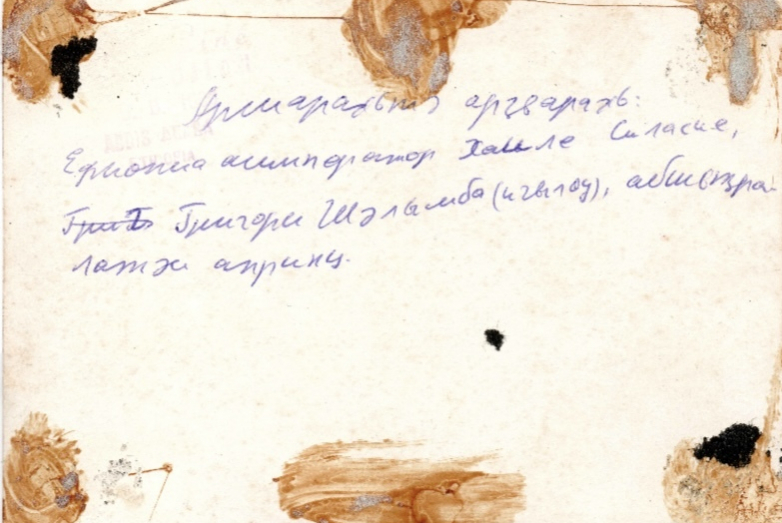

In Ethiopia, the second largest African country, the standard of living was low. In 1936, it was occupied by Italian fascist troops, who managed to be expelled only four years later. By the time the Second World War ended, almost the entire population of Ethiopia was extremely poor, moreover, illiterate, and there was a high infant mortality rate. Emperor Haile Selassie I led the state: he was the last emperor of Ethiopia, who came from the legendary dynasty of the descendants of King Solomon. Grigory Shulumba became friends with his eldest son, Crown Prince Amha. The imperial family often invited the diplomat and his wife to dinner parties and more than once visited the Soviet diplomatic mission.

Under the leadership of Grigory Shulumba, the Soviet mission built a modern for that period hospital in Addis Ababa. By the way, the eldest daughter and son of Grigory Sergeevich were born in this hospital. The diplomat visited Egypt, Iran, Italy and the Vatican on the Mission's business.

In an essay about Grigory Shulumba dated September 1991 in the newspaper "Republic of Abkhazia" the following story is given from that time: "A lot of servants from among the local residents worked at the Mission. Grigory Sergeevich taught one of the people French and literacy. Arriving years later in Moscow, this man tried to find his teacher, but at that time he was in disgrace. For fear of harming him even more, the visitor from Ethiopia stopped searching. This became known only many years after the rehabilitation (Grigory Shulumba - ed.)".

In disgrace

In 1949, Shulumba was recalled to Moscow and faced a number of slanderous charges.

"After returning to the Union, I faced a number of slanderous accusations, which I could not admit, because I did not do this," Grigory Shulumba recalled.

Grigory Sergeevich was accused, among other things, for connections with the British agent Avetis Terzyan, who was the official representative of the Armenian Committee in Ethiopia and who, along with other members of the Armenian Committee, was invited to official receptions of the Diplomatic Mission. The mission regarded them as active organizers of collections of aid to the front during the Great Patriotic War. Shulumba was also accused of "loss of a living person", meaning that a nurse from a Soviet hospital in Addis Ababa married an Italian, and the Ethiopian authorities did not extradite her.

The case of Grigory Shulumba was considered by the Collegium of the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs, chaired by the Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrei Vyshinsky, who is now known to be one of the key figures in the repressions of the USSR, and then by the Collegium under the Communist Party. There was only one verdict - dismissal and expulsion from the party.

"Why didn’t you learn Georgian?"

In the summer of 1949, Grigory Shulumba and his family returned to Abkhazia, to Gagra, where he hoped to get a job as a history teacher at a school.

"I applied to the Department of Public Education of the Gagra district. The inspector of the education department asked if I knew Georgian. To my negative answer, there was again the question - why I did not learn the Georgian language. I answered him that, while in Abkhazia, I studied Abkhaz as a subject, and the rest of the subjects in Russian. After five grades, I studied in Leningrad, where I graduated from high school and university," Grigory Sergeevich recalled.

The summary of that interview turned out to be disappointing: "You will have to go to Russia, where you studied."

Then the Shulumba family left first for Moscow, where the father of the family was able to get a job at a factory in the supply and marketing department, and after some time moved to Central Asia, to his wife's homeland. In the city of Yaipana, Fergana region, the former diplomat became a schoolteacher and earned his living by doing this job. Already after the death of Stalin and the abolition of the cult of personality, in 1955, Shulumba was allowed to move to Abkhazia, and a year later, they were rehabilitated. The diplomat was offered to return to the Foreign Ministry, but pride did not allow him to accept this offer.

In Abkhazia

Until his retirement, Grigory Sergeevich worked in schools in the Gudauta district. He was the head of the eight-year Russian school in Gudauta, and then led the First Abkhazian secondary school, later he headed the eight-year school in the village of Dzhirkhua, where he worked until 1986.

In 1960, Grigory Shulumba was reinstated in the party. It was important and fundamental for him. "I never had a reprimand or a remark about the party and the Komsomol, in which I was from 1927 to 1931," he wrote about himself.

The grandson of Grigory Shulumba Zurab Bzhania recalls his grandfather as a modest man who never boasted of either his education or his bright career. He was a respected man, he was trusted to resolve disputes and he was consulted with. Grigory Sergeevich did not talk much about his past work, because this is not customary among professional diplomats.

to login or register.